So……..It all began one day when I was working in the newsroom at Radio Bristol. I`d been a reporter there for about a year – lots of early morning news shifts interviewing local county councillors interspersed with the occasional opportunity to be a trainee DJ – which in those days was what I thought I wanted to be. So one of my colleagues tells me that he met a guy in the BBC bar last night who`d just moved down from Newcastle to be a producer in regional TV with the idea of doing a new show. He was looking for presenters and the show was going to be about local bands, real ale, architecture, theatre, cinema etc and have Auberon Waugh (a right-wing comic journalist who lived in Somerset now long dead) doing funny pieces about that week`s news. Why that unusual combination? Because they were the things that the producer David Pritchard was most interested in, and this was going to be his show. (In those days the BBC was much more about individual producers` passions – there were no anxious executives looking over the creatives shoulders). “You ought to get in touch”, said this mate of mine.

Next day – trying not to look too keen – I did and we arranged an audition in the Points West studio. It was just me standing there in front of a camera with Pritch (who was quite a bit older than me and a fat bugger even then) telling me to “talk about anything I wanted to.” I thought it advisable to stick to music. Until then my every waking moment had been listening to, playing or reading about music, but only as a hobby; I never thought I could make any money out of it. Pritch was new in town so couldn`t have seen many local groups yet and so I mentioned a few of the more outlandishly named combos (The Gl*xo Babies sounded particularly cool I thought, though I can now admit that I`d never actually heard them play) and tried to sound as though I knew what I was on about. Pritch seemed happy enough and promised to let me know after he`d seen more people.

Weeks went by with no news. I didn`t want to ask, in case it was a “No” but made myself a promise that if I got the job I`d buy myself a leather suit from Paradise Garage – a shop selling Johnson clothes I`d just discovered in the bus station underpass (I`m sorry about the leather thing ok, but all those years of Jim Morrison and The Doors had left a scar). More weeks went by. One day I thought “This is crazy”, confronted Pritch in the canteen and asked him whether I`d got the job or not. “Of course,” he said “Didn`t I tell you?” This was a typically exasperating response from a man who I went on to have an abrasive, but creatively challenging, relationship with for the next 6 years –indeed we`re still friends to this day despite his unreasonable fondness for The Stranglers.

The show was scheduled to start in a few weeks time, but things didn`t go well. Pritch selected a co-host (who I`m afraid I can only remember was called Debbie something) and when a friend of mine saw us together he asked if this new programme was going to be called “The Ugly Show” – and he wasn`t talking about Debbie. Worse, I discovered that Pritch intended to call the programme “The Rectangular Picture Machine”, a truly naff name by anyone`s standards, and much, much worse still had chosen music by The Electric Light Orchestra as the theme tune. God help us.

On my totally uninformed recommendation The Gl*xo Babies had been recorded (again in the Points West studio) but I have a dim memory that we`d also recorded a session with the insensitively named “Spics” who featured lead singer Mike Crawford even then in full proto Rock God attitude and we decided to run them first. When the first show was broadcast I was living near The Coronation Tap and as the credits rolled went there to drink as much cider as they would sell me. This was a truly horrible programme, I was convinced. Getting involved had been a career disaster and I was doomed to be a laughing stock for the rest of my life. Worse, someone recognised me in the pub as being “That bloke off the telly”, a phrase I was to get used to but never liked. Next day the TV reviewer in the Bath Evening Chronicle said I was the sort of presenter who would leave an oily stain wherever I sat. Thanks Pritch.

I really only continued with the show because I`d signed a contract I couldn`t escape from, and the fact that the tiny production team were good people who were fun to be around and the crazy workload didn`t give us much time to get precious. The team finally settled down to being just me, Pritch, two directors called Steve Pool and Alan Lewens, and two programme assistants, Lisa and Phillipa – that was all we had to make runs of twenty shows at a time so we were shooting and editing items every week for the next programme.

We only really managed to make the show by beating the BBC system

- because through some loophole we could “borrow” a London film crew for free (and everything outside had to be shot on film in those days there was no lightweight video) we used to make up local excuses for getting interviews with national and even international names. Debbie Harry, I remember, had an auntie in Totterdown, Pink Floyd`s David Gilmore had been to school in Bedminster. Honest.

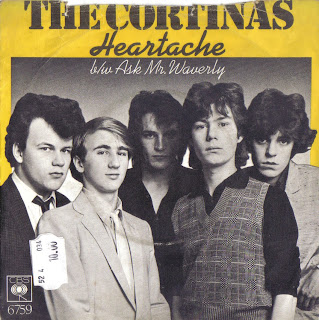

And I suppose the show gradually got better. We made a lot of programmes I`d eventually look back on with some pride. The audience took us to their hearts. Auberon Waugh (or Bron as we got to know him) became increasingly edgy despite an almost total inability to read autocue. His scripts were so contentious that they all had to be cleared by lawyers at the very last minute – hugely predating Have I Got News For You. All the local bands were queuing up for a bit of TV exposure they hoped would get them a record deal (stupid really – all of my experience has taught me you should play music for your own enjoyment not in the hope of getting famous or rich – it hardly ever works). I`d spend most nights down at venues like the Bristol Bridge, The Granary, Trinity Hall, the Bier Kellar at The Hawthorns Hotel (where I interviewed The Clash once) etc trying to find the next big thing. Automatic Dlamini, Talisman, The Electric Guitars, The Cortinas, Juan Foot `n the Grave, The Crazy Trains all competed for a chance to shine. So did a group from Bath called Graduate, all done up neat and tidy in suits. The two singers were called Curt and Roland who later ditched the others in the band and changed their name to Tears for Fears, named after Roland`s obsession with Primal Therapy that he and I discussed during the recording. I spent many, many nights watching local bands in draughty halls – most of the time on my own and being taken the piss out of by whoever was on stage (if I`d been stupid enough to let them see I was there). Best joke; “That Andy Batten-Foster must be clever to get that cat to stay on his head”.

Personal highlights from those days include getting to know XTC`s Andy Partridge (who I still consider a musical genius) who made us a very funny, affectionate and typically quirky little film about his home town Swindon, and, of course, the infamous Stranglers night at The Granary.

This night deserves a paragraph or two of its own. Pritch and Steve had somehow got to know Hugh Cornwell and Jet Black (Steve used to drink cider with Hugh in some place outside Bath that was more like someone’s tiny sitting room than a proper pub) and I think invited them to perform on RPM only because they expected to be turned down. When the opposite unexpectedly happened, they agreed and we suddenly had to take the idea seriously, a certain level of panic set in. We`d never done anything this big so didn`t know which venue to choose. The BBC`s rules about making profits out of events were much stricter in those days so we immediately realised it would have to be a free show – and that brought up a whole bunch of new concerns about security and safety.

It`s almost impossible now to imagine how big The Stranglers were in those days so as soon as we announced we were doing it at the Granary both us and the venue were completely overwhelmed by demand for tickets. However much planning we did (and I can only remember it was a lot) came to nothing because when the big night finally arrived it descended almost immediately into total chaos. About three times more punters turned up than had tickets. A lot of them were really hard-core punks and demanded to be let in. We`d built camera platforms so we could get pictures over the heads of the audience but these began to tilt and sway dangerously as soon as the band hit the stage and the crowd began to surge back and forth. We honestly thought either a cameraman would fall into the heaving masses, which would almost certainly rip him apart in their frenzy, or a falling platform would kill some of the crowd. Either way we were in big trouble. Neither disaster actually happened, of course, or I`d probably be writing this from a prison cell, and the funny thing was that backstage after the gig The Stranglers were completely calm. Every show was like this to them.

Pritch and I only ever had two really big and enduring disagreements during the making of RPM – and one of these was about The Stranglers. As I`ve already said, I think his affection for their music is unreasonable, and yet virtually every week he`d want to include one of their songs in the show – usually Duchess – and every week I`d try and argue him out of it. At one point he became so furious that words failed him and instead he threw a telephone at me (and remember these were the days of big, heavy

desk telephones made with metal in them.)

My protests never worked; he and Steve responded by making a film with Hugh and Jet about Men In Black (this was long before the feature film and incorporated the band`s Waltz in Black which Pritch went on to use as the theme tune for all his later films with Keith Floyd, who was also discovered as an “act” during RPM).

The other big disagreement was over The Parole Brothers. These were a local blues and R and B band fronted by Keith Warmington (who played – indeed still plays – an amplified harmonica or “harp” very much after the Chicago style) while the guitarist was Steve Payne – known as the Prince of Darkness. At the time they were by far the most popular group playing on the Bristol circuit and so, not unreasonably, pushed hard for a spot on RPM. I maintained they were completely wrong for the show because the music they played was traditional rather than original and that – despite their obvious popularity – RPM was about showcasing new bands with new ideas and new songs. Every time I came across one of the band – particularly Keith – the debate became rather heated and so Pritch agreed to come along to one of their shows to make a final decision. By the end of the evening I began to feel that the argument was slipping away from me – Pritch was dancing on top of table, blind drunk and singing along to Sweet Home Chicago.

RPM lasted six years. We must have made a couple of hundred shows in all and when it finally came to an end I was working at Radio One as something more like a proper DJ – although funnily enough I never really felt comfortable once I`d got there. I ended up as an executive producer on shows like 999 and Top Gear (I`ll have to tell you all about Jeremy Clarkson some other time). RPM had “found” Floyd who Pritch went on to make a genuine TV celebrity out of, one five minute film about the death of Eddie Cochran in Chippenham was expanded into the first of a long run of full length music documentaries that Alan Lewens made for BBC 2`s Arena, and even now I occasionally, but less and less regularly get recognised as that bloke off the telly.

And, thank god, I never did buy that leather suit.

Andy Batten-Foster November 2010

The word went out a couple of weeks ago. There was to be, for the first time ever, a compact disc of The Cortinas singles, album and Peel Session release. Hard to believe that no-one had thought to put all the recordings on to one CD before, but there y’go. Excitement reigned…well me and Steve Underwood were happy. And the 29th of November saw the official release. I found a copy on the internet for £4.50.

The word went out a couple of weeks ago. There was to be, for the first time ever, a compact disc of The Cortinas singles, album and Peel Session release. Hard to believe that no-one had thought to put all the recordings on to one CD before, but there y’go. Excitement reigned…well me and Steve Underwood were happy. And the 29th of November saw the official release. I found a copy on the internet for £4.50.

A CD that without any apparent effort gives a party and a documentary in the same 74 mins of music. It doesn’t matter that the title years don’t spread evenly over the 14 tracks (just the two Joshua Moses numbers from 1978 & 79 and the rest are 1980-83). Roots reggae predominates and some lovers’ rock keeps the mood sweet in a range of material opening with Black Roots‘s mellow and informative ‘Bristol Rock’ and moving through quintessential examples from Joshua Moses, Talisman, and Restriction. Eight bands and artists are represented, by up to three examples of their work and all are intimately familiar with the ways of reggae music smoking round your brain and tweaking down your backbone. The second half of the album brings in some less mainstream types such as the distinctly Bowie-like ‘Nights of Passion’ by The Radicals ; and Sharon Bengamin’s ‘Mr Guy’ – both capable of making a mark outside the reggae scene ; and the brief, effective 2 min 43 ‘Riot’ from 3-D Production. Other notable pleasures include the upliftingly beautiful keyboard that takes us in and out of Black Roots‘s ‘Tribal War’, the ska warmth of Buggs Durrant’s ‘Baby Come Home’ and the concluding 12 inch mix of Talisman’s’ ‘Dole Age’. Almost everything here is available for the first time since its own era ; and as well as showing how worthy Bristol Reggae is of renewed and wider attention, it tells today’s guitar-soaked public how much we owe to the brass section as trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn and trombone conjure rich Jamaican sound out of thin English air.

A CD that without any apparent effort gives a party and a documentary in the same 74 mins of music. It doesn’t matter that the title years don’t spread evenly over the 14 tracks (just the two Joshua Moses numbers from 1978 & 79 and the rest are 1980-83). Roots reggae predominates and some lovers’ rock keeps the mood sweet in a range of material opening with Black Roots‘s mellow and informative ‘Bristol Rock’ and moving through quintessential examples from Joshua Moses, Talisman, and Restriction. Eight bands and artists are represented, by up to three examples of their work and all are intimately familiar with the ways of reggae music smoking round your brain and tweaking down your backbone. The second half of the album brings in some less mainstream types such as the distinctly Bowie-like ‘Nights of Passion’ by The Radicals ; and Sharon Bengamin’s ‘Mr Guy’ – both capable of making a mark outside the reggae scene ; and the brief, effective 2 min 43 ‘Riot’ from 3-D Production. Other notable pleasures include the upliftingly beautiful keyboard that takes us in and out of Black Roots‘s ‘Tribal War’, the ska warmth of Buggs Durrant’s ‘Baby Come Home’ and the concluding 12 inch mix of Talisman’s’ ‘Dole Age’. Almost everything here is available for the first time since its own era ; and as well as showing how worthy Bristol Reggae is of renewed and wider attention, it tells today’s guitar-soaked public how much we owe to the brass section as trumpet, cornet, flugelhorn and trombone conjure rich Jamaican sound out of thin English air. With a significant 50′s Windrush era West Indian community, the St Paul’s riot in 1980 and it’s earlier history as a port central to the 18th Century transatlantic slave trade, Bristol has been something of a microcosm of the trials and tribulations of the black community in the UK. As such it’s hardly surprising that in the 70′s and beyond the city should have had a thriving reggae scene.

With a significant 50′s Windrush era West Indian community, the St Paul’s riot in 1980 and it’s earlier history as a port central to the 18th Century transatlantic slave trade, Bristol has been something of a microcosm of the trials and tribulations of the black community in the UK. As such it’s hardly surprising that in the 70′s and beyond the city should have had a thriving reggae scene.